Weave, dream, wait, repeat. New discoveries in the Penelope archive.

Dr Zoe Jennings, who was recently awarded her PhD in Classics at Oxford, here unearths some global contemporary tellings of Penelope’s story.

This blog post is about a complicated woman. Penelope, queen of Ithaka, is one of ancient mythology’s most opaque, frustrating and absorbing figures. Emily Wilson opens her translation of the Odyssey with a refreshing acknowledgement of Odysseus’ complexity – ‘Tell me about a complicated man’ – but in recent decades it is the quiet, evasive and self-contradictory agency of his wife that has proved more suggestive to readers and re-tellers. In the Odyssey, Penelope is a slippery and indeterminate character whose motivations are largely hidden to us; she waits, stands still, hides, and gets nowhere, while her heroic husband roams far and wide completing all manner of epic quests. Her story, and her mysterious inner life, are thus radically enticing – a puzzle to fathom, a dream to interpret, an unravelling shroud to stitch imperfectly back together.

Unsurprisingly, it is feminists who can be credited with bringing Penelope centre-stage into the twenty-first century. Since the 1970s, writers and artists have approached her in the revisionist mode, finding ways of deconstructing the character’s idealisation as the dutiful wife and daughter-in-law, upholding her paradigmatic acts of weaving and un-weaving as sites of resistance and independence, and exploring her subjectivity as artist in her own right. A reclaimed Penelope explodes into the twenty-first century with Margaret Atwood’s Penelopiad in 2005, a text which displaces Odysseus as epic hero, centring Penelope’s voice and creative agency. Atwood’s seminal novella can be said to haunt many subsequent Penelopes – not least the Penelope’s Web opera project, which takes its cue from the feminocentric soundscapes created by Atwood in order to explore Penelopean modes of musical, especially vocal, expression. Like many other contemporary epics, The Penelopiad, which mixes narrative, poetic and dramatic styles, explores and invites performance; indeed, Atwood later dramatized it in a 2007 production for the Royal Shakespeare Company and Canada’s National Arts Centre. Perhaps spurred by Atwood’s landmark work, the twenty-first century is crowded with Penelopes in performance and other non-textual media, which this blog post sets out to explore.

As the title of the Penelopiad might suggest, one potentially failsafe way of ensuring Penelope gets her due is by having her replace Odysseus as the central hero of the epic. A work that takes this approach is Current Nobody, a play by Melissa James Gibson that premiered at Washington’s Woolly Mammoth Theater in 2007. Penelope (‘Pen’) is a successful war photojournalist reporting on a distant conflict, while her husband, Od, stays at home to look after their daughter, Tel. The play’s role reversals serve as a way to reveal just how far the plot of the Odyssey relies upon traditional gender roles being maintained. In this ‘modern’ set-up of working wife and stay-at-home husband, the Odyssean plot unravels. Pen, as a working mother far from home, is treated by those she encounters with a misogynistic suspicion that takes her on very different journeys to those of the Homeric Odysseus; Od, meanwhile, is an inattentive father who cannot run a household and weaves upon a toy loom purely to distract himself from the pain of his wife’s absence. Current Nobody might be read as an exposée of the ambivalences and limitations of a feminism that envisions emancipation in terms of a simple role swap, whereby women are supposed to be empowered solely by their proximity to ‘maleness’ and patriarchy.

Indeed, artists in recent years have tended to value Penelope much more for what she offers in terms of an alternative to androcentric forms of narrative, creative production, and subjectivity. In her famous 1990 essay, ‘What Was Penelope Unweaving?’, Carolyn Heilbrun argued that Penelope, faced neither with the ‘masculine’ quest plot nor the ‘feminine’ marriage plot, encapsulates the possibility for an ‘as-yet-unwritten story: how a woman may manage her own destiny when she has no plot, no narrative, no tale to guide her’. Many have taken up that possibility – Penelope not as epic bard like her husband, but a different kind of teller – through play with genre. Indeed, Penelope left the epic scene early on, entering the lyric tradition already in Ovid’s epistolary Heroides, where she is granted new agency, narratorial voice and a generic space in which she can explore the multiple facets of feminine selfhood that remain so obscured when she is in her epic environment.

An interesting contemporary articulation of this lyric Penelope, which foregrounds outward expressions of interiority, is found in song and forms of musical theatre. Penelope’s story has a long operatic lineage, which is underpinned by the relationship between song, interiority and emotional expression. A neat encapsulation of this is Penelope and the Geese, an opera or song-cycle written by Milica Paranosic (music) and Cheri Magid (libretto) in 2019. The piece formulates a meandering sung narrative that, as the makers say, ‘largely takes place in Penelope’s mind’. The all-female creative team saw it as particularly important to challenge the perception of Penelope as chaste and faithful, using the opportunity afforded by song to centre the character’s desire and sexual agency. The structure of the Odyssean epic quest is given a gendered lyric twist: while the singers wend their wandering way through Penelope’s sensual inner life, Odysseus lies asleep and motionless on the stage.

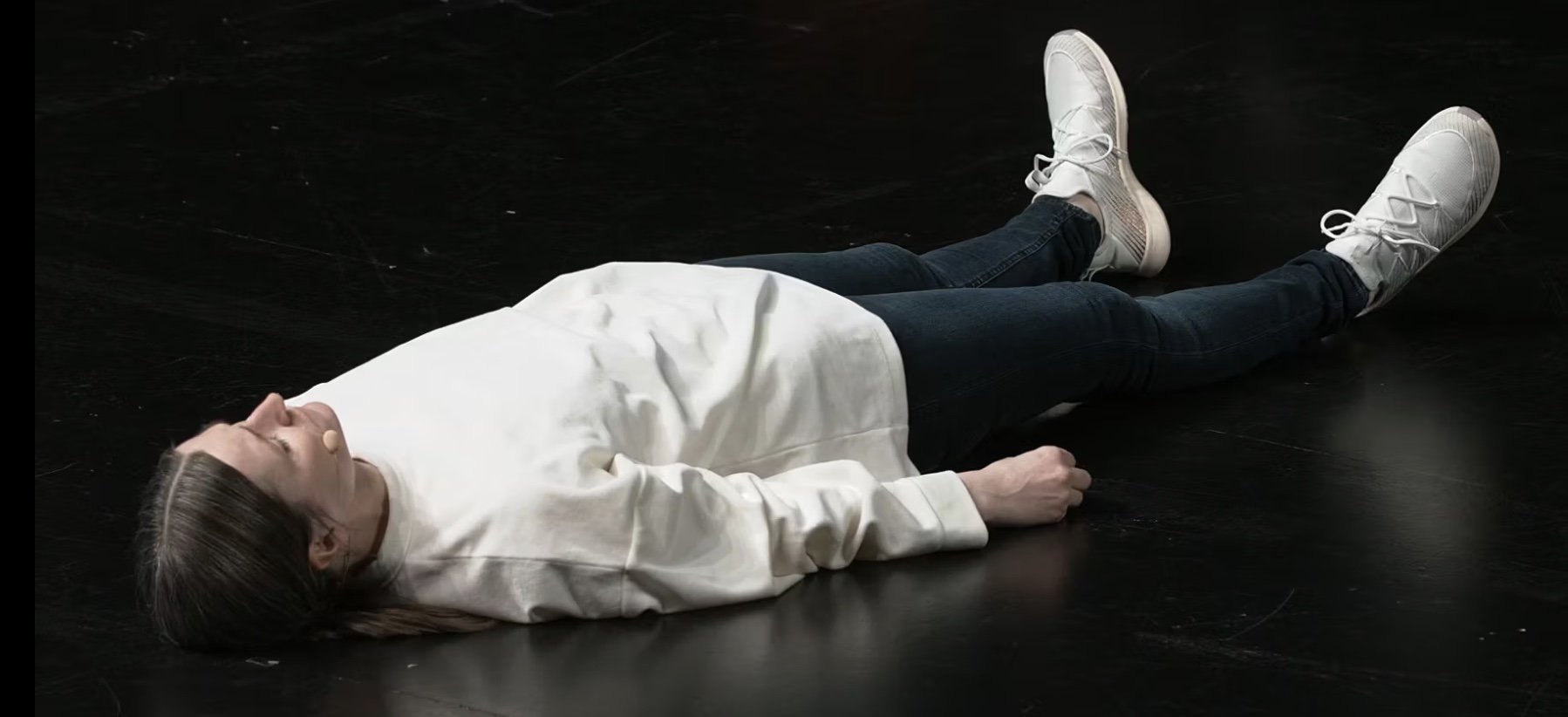

Another musical example is Penelope Sleeps, a piece written and performed by Mette Edvardsen (libretto) and Matteo Fargion (music) in 2019-20. The opera presents itself an ‘opera in essay form’ and stands as a Penelopean subversion both of Odysseus’ nostos narrative arc and of the well-made operatic plot. The work is made up of a series of narrative readings and meditative, repetitive songs that resemble religious lyric poetry, psalmody or perhaps lament. Penelope is refracted through the first reading that Edvardsen gives, about a spider that she encountered in the guest room of her father’s house. Penelope, like the spider, is a lone and industrious weaver (and un-weaver) who is most active at night in the seclusion of her bedroom. Her act of un-weaving becomes a metaphor for narrative fragmentation and non-linearity. Penelope Sleeps thematises the undoing or fraying of narrative, building its atmosphere through polyphonic segments stitched together without logic, and like Penelope, it constantly forestalls any kind of resolution. Homeric epic is thus rendered, in the makers’ words, ‘as vague as a dream from which one has just awakened’. This lyric open-endedness is highly Penelopean, offering a feminine counterpoint to the teleological propulsion of the Odyssey. It shares this, notably, with Barbara Köhler’s 2007 poem-cycle Niemands Frau, which forges a ‘Penelopean poetics’[1] through textual indeterminacy and polyphony, and – while primarily a textual work – is framed in musical terms, twisting the phallocentric grandeur of epic song into a form of feminocentric lyric that foregrounds experience and self-expression over narrative line or ‘homecoming’.

Screenshot from film of Penelope Sleeps (Edvardsen and Fargion)

That such a Penelopean experience might be akin to dreaming is a proposition taken up by the filmmaker Ben Ferris in his 2009 Penelopa, a Croatian-Australian co-production. Cinema, though frequently associated with the epic genre, also possesses lyric capacities that Ferris captures in his moody depiction of Penelope’s tortured inner life. The film has the quality of a dream, using long take shots and temporal distortions to disrupt narrative expectations. It becomes very hard to tell what is real and what is imagined as viewers are immersed into Penelope’s subjective experience, and Ferris induces us to ‘wait’ with her, going nowhere, yet travelling into the wildest corners of her imagination. Sleep, and dreaming, are frequently associated with Penelope throughout the Odyssey – she develops her own theory of dream interpretation and employs the so-called ‘trick of the bed’, both as tests for her husband upon his return to Ithaka. Dreams – unburdened by rational or logocentric forms of narrative– might well be taken up as Penelopean sources of alternative feminine creativity: as Anne Carson writes in ‘Every Exit is an Entrance (A Praise of Sleep)’, ‘Sleep works for Penelope. She knows how to use it, enjoy it, theorize it… sleep is not [Odysseus’] country’. Another piece called Penelope Retold, a theatrical monologue created by Caroline Horton and commissioned by Derby Theatre to respond to their main house production of the Odyssey in 2015, accordingly takes place entirely upon a queen-sized bed, where Penelope – a military wife – waits anxiously, then angrily, for her husband to return.

If the character of Penelope can be said to encapsulate forms of subversion that arise out of otherwise potentially restrictive states – stasis, waiting, sleep, domestic confinement – the pandemic provided ample opportunity for Penelope to come centre stage. The concert theatre piece Penelope began as a concept album written by Alex Bechtel in the first months of lockdown in 2020 while he waited in quarantine to be reunited with his partner. Later expanded into a performance by Bechtel, Eva Steinmetz and Brenson Thomas, this Penelope – again, a predominantly solo piece – talks her audience through a day in her life. In the makers’ words, ‘Penelope is a love letter to all those who feel isolated; to all those who have to wait for something they love, and find agency and power within that wait’. Another such love letter – and more to the point, a literal epistle – was Hannah Khalil’s contribution to Jermyn Street Theatre’s 2020 15 Heroines, a series of adaptations of Ovid’s epistolary Heroides. Khalil’s ‘Watching the Grass Grow’, which takes energy from Ovid’s rather more impatient Penelope, depicts her as a twenty-first century dressmaker waiting for her husband’s return from a team-building weekend in lockdown. ‘Pen’ exercises a quiet rebellion from within their shared suburban home, cutting the cable of her patronising, interfering neighbour’s lawnmower: ‘I can mow my own fucking lawn’.

A rather different strand of contemporary Penelopes highlights the fine line that exists between finding feminine agency in states of immobilisation and undermining it. In the Irish playwright Enda Walsh’s tragicomedy Penelope (2010), Penelope is presented as an entirely voiceless absence. The play takes place in an empty swimming pool on Penelope’s estate, where four men – her suitors – have been living while they attempt to win her love. It is often read as an allegorical representation of the demise of Ireland’s economy in the post-Celtic Tiger era, with the suitors – literal competitors – representing the Irish businessmen involved in the 2008 financial crash, and Penelope as a silent and distant personification of the market, who is testing their loyalty to her. While the play makes important satirical commentary on contemporary Irish politics, it is far from feminist in its use of a female personage to trope a capricious, voiceless cipher.

Another piece about Penelope in which Penelope herself does not really feature is Sam Trubridge’s work Penelope’s Window, which he performed as part of Performance Art Week Aotearoa in November 2023. For three hours a day for three days, Trubridge rowed a dinghy alone around Wellington harbour while reading the Odyssey aloud. Audiences could watch either from the beach, listening to him on Bluetooth headphones, or in town at the main festival venue, through telescopes or a Zoom live-stream. The work constructs the spectator as its ‘Penelope’, looking out at an Odysseus labouring fruitlessly at sea (read: splashing about in the harbour). Though the piece has a feminist and also post-colonial edge in its intention to ‘satirise the white male protagonist of “discovery” narratives’, as Trubridge says, somehow the piece still ends up centring the white male artist, leaving spectators passive witnesses to his futile strivings. Penelope is missing yet again, her story – like in her canonical depiction – becoming a platform for the exploration of the male psyche. What is more, in its attempt to subvert a text associated with the western and colonial ‘canon’, it also sidelines the many local Māori myths that are associated with ocean crossing and discovery.

Sam Trubridge as seen through the camera lens in Penelope’s Window © Robyn Jordaan

As we have seen throughout this post, receptions of Penelope are at their best when she is presented as a real woman, brought forth in all her complexity. One final example, perhaps the most powerful of those explored here, presents an untamed, multifaceted and embodied Penelope whose unruly vitality bursts at the seams. Tatiana Blass’ site-specific installation, Penelope, was mounted at the Chapel of Morumbi in the artist’s hometown of São Paulo in 2011. The work consists of a loom, which sits at the chapel altar, and a wild mass of red yarn, woven into a long red carpet that leads to the door. But on the other side of the loom, the yarn has been threaded chaotically through several holes in the chapel walls; a walk around the building reveals an entire churchyard covered in tangled and flesh-like threads. The viewer is invited to consider whether the yarn is being woven together, or messily taken apart. The use of the red thread is perhaps a nod to another wily but abandoned woman of Greek myth, Ariadne.

As a work of fibre art, Blass’ piece honours and elevates a ‘low’ form of cultural production often denigrated as ‘women’s work’, but which can become a site of expressive resistance, foregrounding the feminocentric powers of the tactile, embodied and experiential, over western art’s phallogocentric elevation of ‘pure’ forms. Indeed, the piece’s poetics of unmaking are a clear act of feminist protest against the sanctity and unity of the space. The abject image of red thread leaking through the holes in the walls takes aim at the patriarchal ideals of bodily coherence and containment associated with Christianity, resisting the church’s historical punishment and marginalisation of female bodies as wayward and impure. A feminocentric creativity and lifeforce, here, is instead excessive, turbulent and messy. Penelope’s expressive powers refuse to be restrained, transversing the stony partition between private and public realms, inner life and outer persona. Spreading out into the garden, the piece presents Penelope at her most joyful amongst the unruly growth of plant and insect life, opting for an eco-feminist proximity to the Earth rather than Christian transcendence of it.

[1] See Barbara Clayton’s A Penelopean Poetics: Reweaving the Feminine in Homer’s Odyssey, 2004.