Pushing Back: Odysseys in Folkestone

By Emily Pillinger

On Wednesday 15th November 2023, an unusually sunny day, the UK Supreme Court released their judgement on the legality of the government’s so-called ‘Rwanda policy’. The policy proposed to deport to Rwanda people who sought asylum in the UK after entering by means that have been identified as illegal. The government had argued that Rwanda is a country with the capacity to process petitioners’ claims to asylum fairly, and to provide a safe permanent home for those petitioners if their claims to asylum were upheld.

The Supreme Court ruled in its conclusion (p. 56) that ‘there are substantial grounds for believing that the removal of the claimants to Rwanda would expose them to a real risk of ill-treatment by reason of refoulement. It was accordingly correct to hold that the Secretary of State’s policy is unlawful.’ In other words, the judges believed that there was a risk that the Rwandan courts might forcibly and unjustly return asylum seekers to countries in which they would face ongoing persecution. The importance of avoiding any danger of ‘refoulement’ – pushing people back to places where they will face danger – is a fundamental principle of international law.

On that very same day, by coincidence, the Being Human Festival and King’s College London were supporting a collaborative workshop in Folkestone with a group of men who could have been directly impacted by the Supreme Court judgement. ‘Writing Home: Myth, Letters, and Refugee Well-Being’ was an event shared with men who are all living in UK Home Office accommodation, having travelled thousands of miles from their homes to enter the UK asylum system. We gathered in a local drop-in centre, a cosy church hall whose drafty windows and outside toilets are offset by warm radiators and a kitchen stocked with cake and hot drinks.

‘Writing Home’ was designed and run jointly by art therapists and creative artists from the charity Art Refuge (Bobby Lloyd, Miriam Usiskin, Josie Carpenter and Aida Silvestri) and by two ancient historians and literary critics from King’s College London (James Corke-Webster and me, Emily Pillinger). We were also joined by Cheryl Frances-Hoad and Jeanne Pansard-Besson, the composer and writer behind ‘Penelope’s Web’.

Art Refuge uses an innovative method to support people in transit and in crisis. They gather participants around what they call The Community Table. On this table they curate a range of objects that are evocative, stimulating, and above all tangible. The table might host, for example, a pile of building blocks, some plasticine, a few postcards of famous landmarks, some fruit, a few bottles of spices, a book of poetry in different languages, a couple of typewriters, and one or two large maps. Bobby Lloyd and Miriam Usiskin have described how the items on The Community Table fostered activity in their workshops with participants in Calais:

‘There was a symbiotic relationship between the art materials we provided and the people using them. The physicality of being able to manipulate something seemed to elicit embodiment, often not needing to be explained or be put to words. This physicality enabled intentionality – you have control, you can knock it down, build it up, place it where you wish to. Crucial to the group is allowing the image or construction to hold meaning at many levels. These meanings may or may not be understood by the maker at the time, but with the presence of others, our and their attentiveness can hold and contain these meanings and potentiality.’

James and I had both studied the Art Refuge therapists at their remarkable work, and James’ Letters of Refuge exhibition at King’s was founded on his appreciation of how The Community Table can create a space for togetherness, creativity, and communication amidst the trauma of displacement. He wrote of that exhibition:

‘The main goal of the exhibition was to put the voices of those who have experienced displacement and persecution – which have been and are largely ignored, whether because of the passing of time or the rhetoric of politicians – front and centre.’

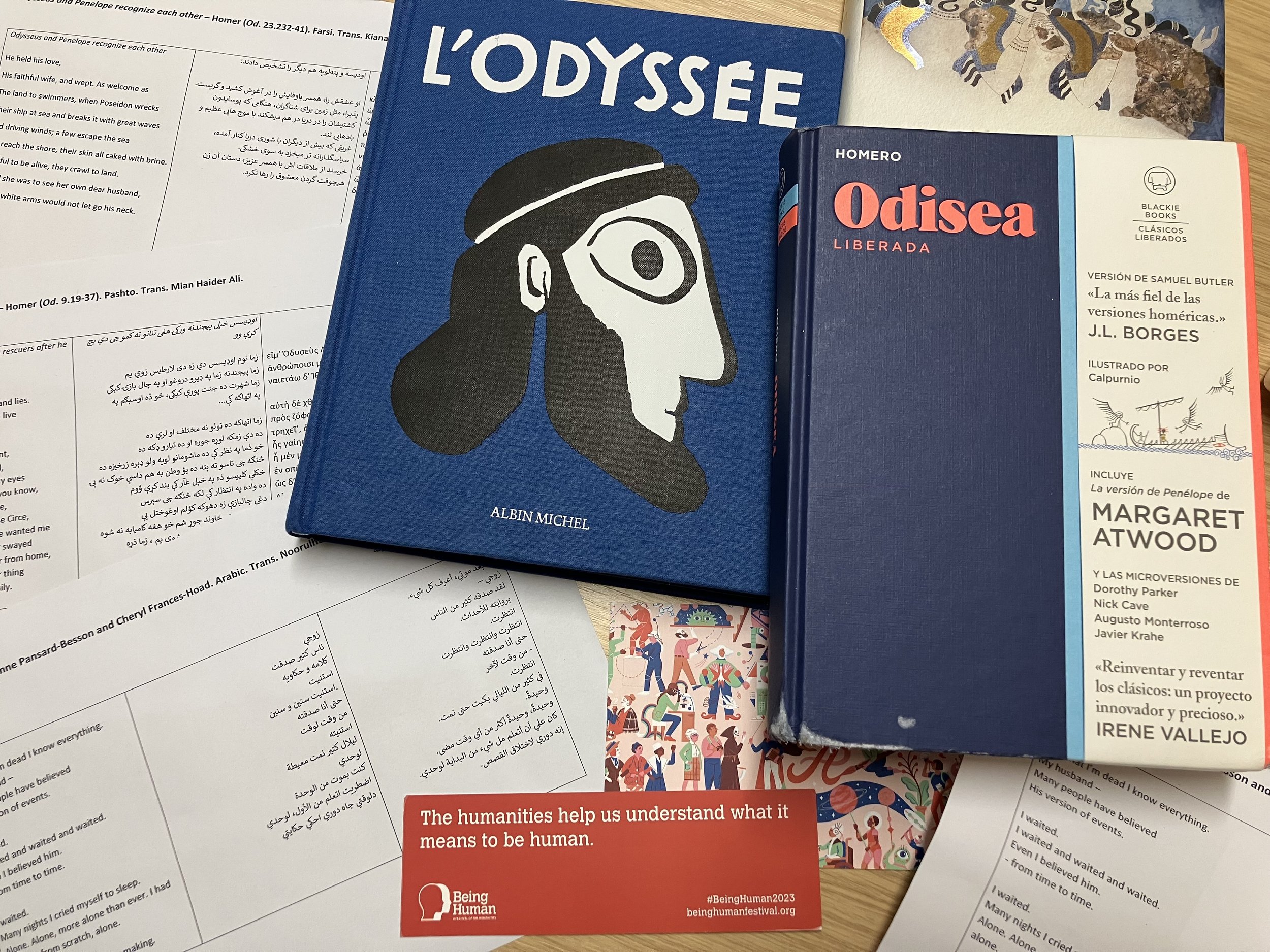

For ‘Writing Home’ we decided to contribute to the table a compilation of sources that would offer snapshots of the narrative of displacement experienced by Odysseus in Homer’s Odyssey. We wanted to focus not just on Odysseus’ travels, but also on the feelings of his bereft wife Penelope and their communications. We knew that it would not be appropriate to spend a long time introducing the story, so we began by collecting copies of the Odyssey in different European languages likely to be spoken by participants, treating the editions as much as objects to handle as books to read. Our colleague Rosa Andújar directed us to a Spanish edition based on Samuel Butler’s English translation (Odisea Liberada) and we found a French edition with powerful, timeless and dreamlike watercolour illustrations by Jean-Marc Rochette (Odysée, trans. M. Meunier). We also bought Gareth Hinds’ graphic novel that tells the story of the Odyssey.

In the lead-up to the event, we invited into the project some students from King’s College London who had learned English as a second or further language. We paid these students to translate into their mother tongue some short passages from the ancient poems and from Jeanne’s libretto (‘Asphodel’). The passages included a part of Penelope’s letter to Odysseus, as imagined by Ovid in Heroides 1:

You are a conqueror, and hard-hearted, but you are missing and I cannot know

why you are delayed, or where in the world you are hiding.

If anyone anchors a foreign ship in our harbour,

I question him endlessly before he leaves,

and give him a letter written by my own hands

to give to you, if he ever sees you anywhere.

…..

As it is, I don’t know what to fear; instead I crazily fear everything,

and the world is an empty slate for all my worries.

Whatever dangers there are at sea, whatever dangers there are on land,

I imagine that they could be the reason for such a long delay.

While I’m stupidly panicking about these dangers, you may have fallen

in love with a foreigner. It wouldn’t be untypical for a man like you.

Ovid Her. 1.57-62, 71-76, trans. E. Pillinger

We also included a passage from the moment in Homer’s Odyssey when Odysseus and Penelope finally allow themselves to acknowledge each other:

He held his love,

His faithful wife, and wept. As welcome as

The land to swimmers, when Poseidon wrecks

Their ship at sea and breaks it with great waves

And driving winds; a few escape the sea

And reach the shore, their skin all caked with brine.

Grateful to be alive, they crawl to land.

So glad she was to see her own dear husband,

And her white arms would not let go his neck.

Hom. Od. 23.232-41, trans. E. Wilson

After a couple of weeks our amazing students, either individually or in groups, had translated these passages and others into Arabic, Farsi, and Pashto.

For me – that is, someone who has spent their whole career learning to make ancient Greek and Roman texts feel familiar and comprehensible to Anglophone audiences – it was a revelation to see and hear the Odyssey in the process of being made familiar and comprehensible to those who speak and write other languages. The passages were turning into sounds and scripts that were unfamiliar to me; they were being domesticated by and for our bilingual students. It was a sonic, visual, and semantic transformation that handed the text over to the linguistic mastery of students, not their teachers. Those students retraced the story of Penelope and Odysseus through the language not of their formal education, but of their family home, diving into the linguistic soundscapes of early childhood. (We will be writing and recording some separate material about this remarkable experience, and introducing new languages to the project: watch this space!)

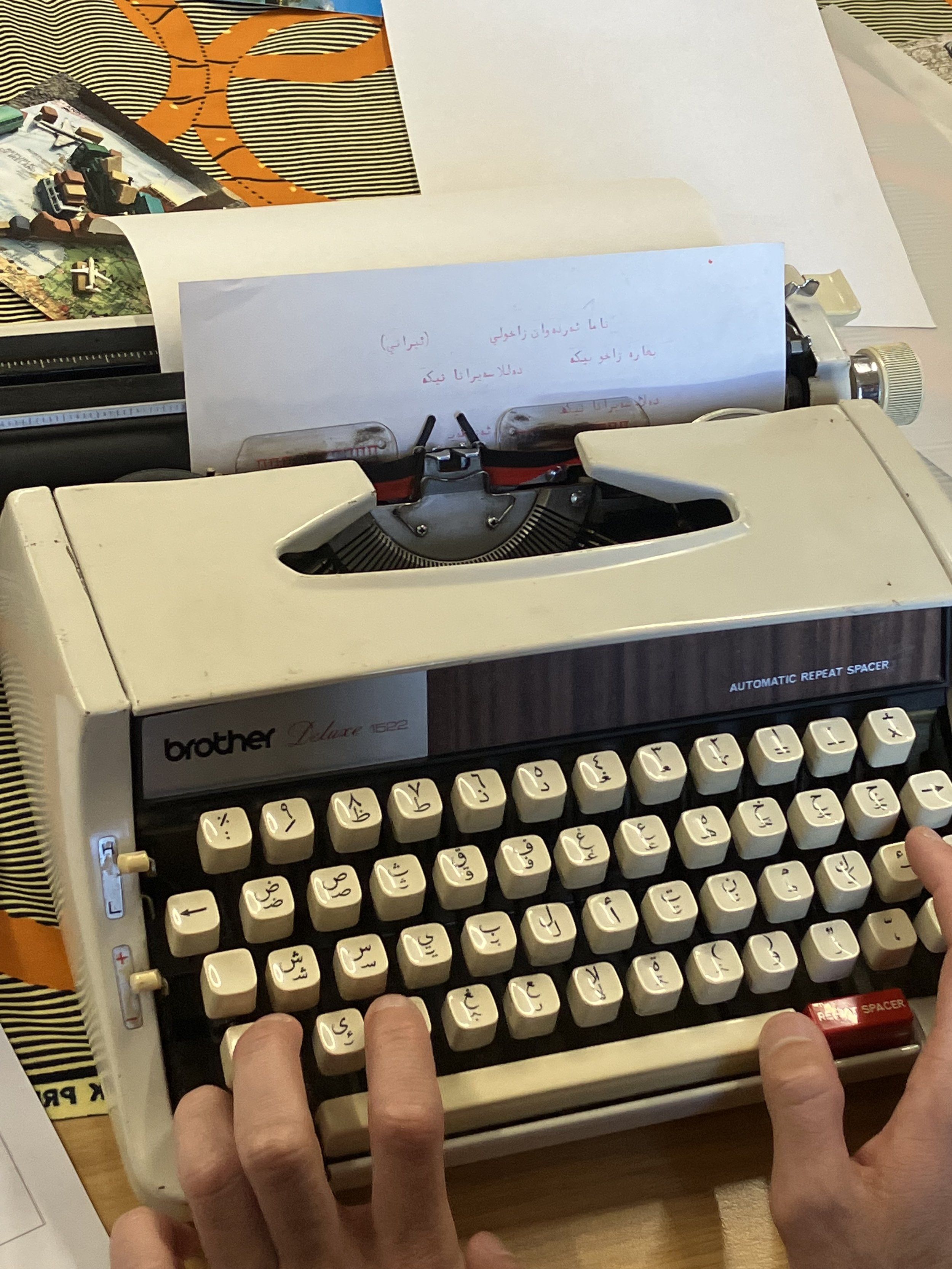

When it came to the day of ‘Writing Home’, we laid out the books and translations on a table that Bobby and Miriam had decorated with beautiful fabrics. They had also brought two typewriters to our version of The Community Table: one that could write in the Latin alphabet, and one in Arabic script. There were Being Human Festival blank postcards and pens, and some building blocks that could be constructed into columns with decorative capitals. We also had a computer playing a slideshow of images from Ithaka, Odysseus’ home island in the Ionian Sea, where Penelope spends her whole married life, and we played Cheryl and Jeanne’s piece ‘Asphodel’ quietly through speakers in the background. Then on a separate, smaller table we laid out a large map of West Asia, North Africa, and Europe. We had deliberately chosen to print a map with the physical geography of these spaces depicted, but with all political markings removed. Over the map we laid a transparent plastic tablecloth on which anyone could draw with marker pens.

When the doors were officially opened, the little church hall gradually filled with small groups of men, some coming in a little tentatively, some more confidently. One was carrying a large musical instrument case. They gathered initially around the large table with texts and objects, often in groups of shared language, country of origin, or ethnicity. There was a large group of Kurdish men, although the members of the group had come from several different countries that house Kurdish exclaves. The atmosphere was muted, with people tinkering with the most accessible objects, chatting quietly, and getting cups of coffee. Then conversations started to bloom, and the room’s emotional temperature started to lift.

In my experience of The Community Table, conversation between participants and volunteers can be difficult, but communication is easy. There is no need to talk, as the objects on the table are the focal point. Yet it is not long before people make observations and start engaging with each other. Knowledge of English varies a lot, but everyone is desperate to try. Some participants will become unofficial translators for others. While some of the participants that day were initially reticent – particularly the oldest and the youngest (perhaps the most tired and the most traumatised?) – in general the men were eager to talk, to share, to explain their lives and journeys. Many were aware that they were not being fully understood, but talked on regardless, almost compulsively. One young man showed me photographs of his two beautiful little siblings back in Afghanistan, a boy and a girl. He also had a photograph of himself when he started work as an assistant in a pharmacy, aged 12. He had had dreams of becoming a pharmacist himself, but was frustrated that at the age of 22 he had still not managed to access the education he needed, and could currently neither study nor work while he was stuck in the holding pattern of the asylum system.

In these exchanges technology, ancient and modern, is a gift. Smartphones help us to translate awkward words, or to move from text in one script to another. They let us look up local landmarks, famous historical objects, beautiful landscapes that are missed. One Iranian man talked to me about Shiraz, while we admired photos of the ruins of Persepolis. The sound speakers become part of the conversation. Our new Kurdish friends wanted to play some songs by a young Kurdish-Iraqi singer persecuted and ultimately murdered by Saddam Hussein in the early 1980s, Erdewan Zaxoyi. So Penelope’s song from the Underworld, lamenting the endless fields of ‘Asphodel’, was replaced by Zaxoyi’s lament in exile for his lost country: ‘Kurdistan bare gran’, Kurmanji for ‘Kurdistan is great’ (with thanks to another intervention by Google Translate).

As the music got louder, and lunch arrived from a local Turkish restaurant, people started to move around more. The food was delicious, plates were scraped clean, and the energy levels rose considerably. As the Kurdish music on the speakers continued, some of the more confident men joined in the recording by playing some drums that local volunteers had provided, and others started dancing dabke in a line, circling the room. It was neither cautious nor raucous, neither self-conscious nor particularly performative. It was spontaneous, slightly boisterous, and a lot of fun, with anything from two to half a dozen people getting involved as the line wound between the tables.

More traditional technology is no less powerful in making connections. As more of the church hall was occupied and explored by the dancing, people started to look more closely at the unmarked map on the separate table. On the map I had roughly drawn in black marker pen one interpretation of the route of Odysseus’ journey across the Mediterranean in the Odyssey. Looking at it, James had noted how remarkable it is to see how much of Odysseus’ travels involve him not exploring, but being pushed back, circling round, trying again.

A group of men gathered around the map and started pointing out where they had come from, and how they had travelled to the UK. James encouraged them to use the pens, and they began by pinpointing the countries they travelled through. They mostly avoided drawing borders, but instead wrote in the names of the countries and cities through which they had passed. Hearing and seeing their stories was like reading an ancient itinerary, or describing a train journey: it was marked by a list of stops. Lines carved out direction of travel, and circles – often reinscribed, drawn over again and again by the same or different hands – marked pauses. Pauses tended to mean problems, as Bobby later told me.

In the ‘Writing Home’ workshop most participants had begun their routes to the UK from Syria, Iran, Iraq, or Afghanistan. They had taken many routes: via Turkey, Belarus, Italy, or Bulgaria. Some had spent months, even years, in Greek camps. Others had been forced to camp out in freezing Bulgarian forests. Some had been injured working in factories en route. Others had been attacked by police dogs. Like Odysseus, many had been forced to double back at least once, to the first European country in which they had been fingerprinted. Fingers and pens circled the English Channel round and round, over and over again. All of the participants had crossed the Channel, but some had had to make multiple attempts after their boats got into trouble and at least one had been rescued from the sea after spending an hour struggling in the water – the water whose waves crashed just 50 metres away from the drop-in centre. A tiny boat sculpted out of plasticine, with a human figure in it, floated around the map. It retraced the ancient and modern sea routes, pushed back and forth across the Bosphorus, the Mediterranean, and the English Channel.

The only country whose borders we found left on the map at the end of the day was a country that doesn’t officially exist: the Kurdish participants had drawn a notional Kurdistan. The borders had been laid out with great precision, encompassing the different populations currently divided among different modern nations. But the country’s outline was oddly placed in the expanse on the map that is technically Saudi Arabia. There was no space on the map for it where it ‘should’ have been.

During this time, Spotify and the speakers had gradually been replaced by live music. While someone had been playing drums to accompany the recordings of Zaxoyi’s songs and the dabke dancing, a new sound was now emerging. Bassam, a musician who spoke Arabic and Amharic having spent time in Saudi Arabia and in Eritrea, had begun to play the oud he had brought in that large instrument bag at the beginning of the day. There was some shushing, then Josie, a poet and member of Art Refuge, who had learned an Amharic song from Bassam the previous week, sang it with him in a mesmerising impromptu performance for everyone in the room.

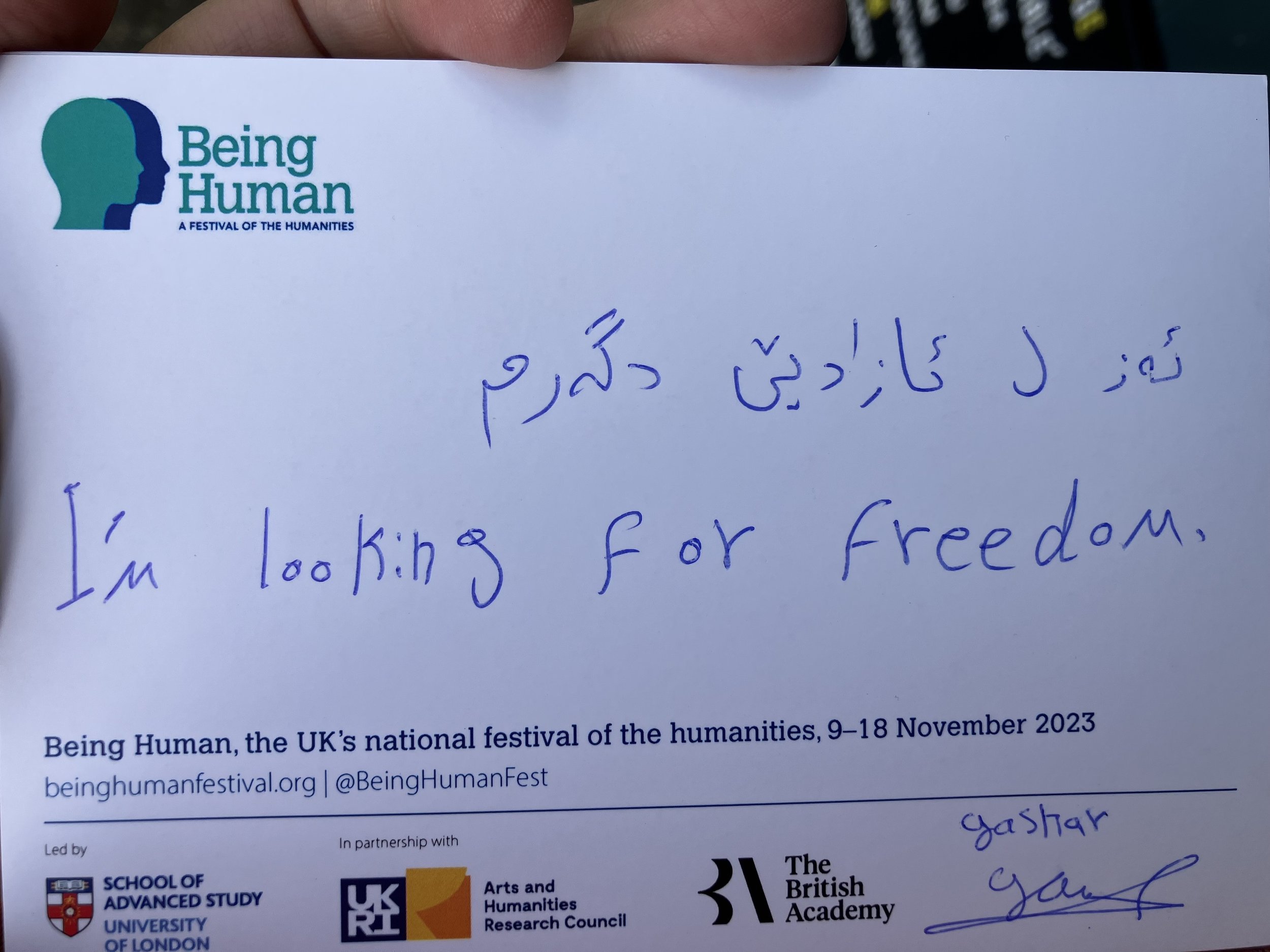

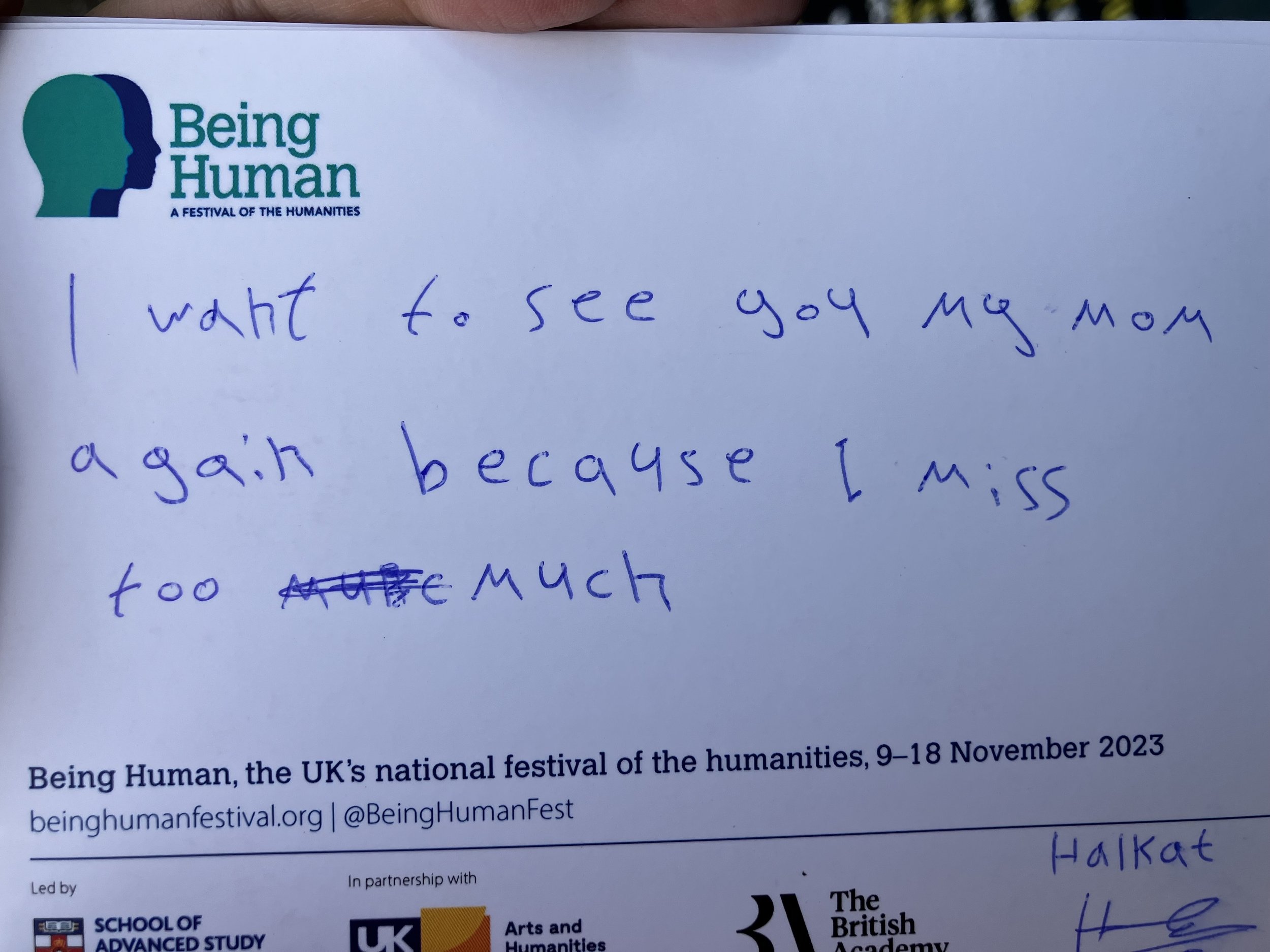

Following this moment of stillness I took the opportunity to give out a few postcards to the participants, and asked them if they would like to write something about their home, in any language. It was also time to bring the event to an end: the participants slipped the cards back to us, a little shyly at times, before leaving the hall. I found myself making gestures that I don’t think I’ve used before, and I’m not sure quite what I meant by them. I was putting my hands together in a prayer form to express thanks, but also crossing my hands over my heart. I think I was trying to show how profoundly touching and meaningful it was for them to have shared their feelings about home with us, how privileged I felt, and how grateful I was. I could only understand some of the writings on the cards, but they already felt like immensely precious artefacts. Many of the men made the same gesture in response as they left – perhaps out of politeness, perhaps mirroring my emotion.

In the vacuum left after the participants had left, as we were beginning to pack up, I noticed that some tall columns had been built by a small, quiet group of young Afghan men who had kept themselves a little apart during the workshop. Bobby and Miriam told me that earlier in the day they had tried placing the columns in front of our slideshow of Ithaka, to make it look like their constructions were placed in that landscape. Some little human figures had been placed on the very top of one column, just like the human figure in the tiny plasticine boat.

In the article I quoted from above, Bobby and Miriam urged us to allow such constructions to hold many meanings. ‘These meanings may or may not be understood by the maker at the time, but with the presence of others, our and their attentiveness can hold and contain these meanings and potentiality.’

I had been wondering: were the figures stuck up there, stranded, facing a perilous leap down? Or were they standing proud, having made it to where they wanted to be?

Maybe both could be true.